June 16, 2009

Posted at 5:25 pm (Pacific Time)

Late last month, Gallup released findings from a new poll demonstrating that opposition to marriage equality is higher among American adults who say they don’t know anyone who is lesbian or gay.

The survey, which was conducted earlier in May, found that Americans oppose legalizing marriage between same-sex couples by 57% to 40% . That margin hasn’t changed notably since a previous Gallup poll about a year ago.

When the May sample was split into those who said they have a gay or lesbian friend, relative, or coworker (58% of the sample) and those who didn’t (40%), the differences in marriage attitudes were striking.

The latter group registered overwhelming opposition to marriage equality — 72% opposed it whereas only 27% favored it. Within this group, 63% said legalizing marriage for same-sex couples will change society for the worse, compared to six percent who said it will change society for the better. 30% believed it won’t have any effect on society.

By contrast, respondents reporting personal contact with a gay man or lesbian were almost evenly split — 49% supported marriage equality and 47% opposed it. They were also divided over whether marriage equality will change society for the worse (39% believed it will) or will have no effect (40% believed this). Only about one in five said it will change society for the better, but that percentage was more than three times higher than the comparable figure for respondents without a gay or lesbian friend, relative, or coworker.

Consistent with past research, the poll found that attitudes toward marriage equality are linked with a person’s political ideology, and that liberal respondents were more likely than their conservative counterparts to personally know gay people. But Gallup found that the correlation between personal contact and opinions about marriage remained significant, even when political ideology was statistically controlled.

But Why Only 49%?

The Gallup report prominently characterized the survey as showing that “Opposition to gay marriage [is] higher among those who do not know someone who is gay/lesbian.”

But we might well ask why there wasn’t greater support for marriage equality among poll respondents with gay or lesbian family or acquaintances. Why did only about half of that group support marriage rights? After all, research conducted over the past two decades has consistently shown that heterosexuals are less prejudiced against gay people if they know someone who is gay, and such prejudice is closely associated with opposition to marriage equality. (Data are lacking on how knowing a bisexual man or woman affects sexual prejudice among heterosexuals, but there’s reason to believe that the pattern is similar.)

My own reading of the research literature suggests that the strength of the correlation between prejudice and mere contact has diminished in recent years. A decade ago, knowing whether a heterosexual had a gay or lesbian friend or relative provided a very good indication of that person’s attitudes toward gay people in general. Today, personal contact remains a good predictor of prejudice, but it’s not as reliable as it once was.

I believe this diminution of the predictive power of mere contact may provide insight into what it is about contact that links it to nonprejudiced attitudes. My hypothesis is that the key variable isn’t — and never was — whether heterosexuals simply know a gay man or lesbian. Rather, what’s always been critical is the nature of that relationship. Perhaps the central variable is whether or not heterosexuals have talked with their gay friend or relative about the latter’s experiences and, in the course of those discussions, developed a better understanding of and more empathy for the situation of sexual minorities.

My hunch is that in the past, when most gay men and lesbians were highly selective about coming out, it was sufficient for researchers to simply ask heterosexual survey respondents whether they knew gay men or lesbians. If they had a gay friend or relative, more likely than not, they’d found out directly from that individual about her or his sexual orientation. Or, subsequent to finding out through some other means, they talked about it with her or him.

Today, by contrast, gay men and lesbians are more publicly visible. Many more heterosexuals probably have the experience of knowing that a relative, friend, or (especially) a coworker or neighbor is gay without ever having discussed it directly with that individual. Thus, knowing the details about a heterosexual person’s contact experiences is more important today than it was a few years (or decades) ago.

Some Data

This hypothesis is partly supported by data I collected in a 2005 telephone survey with a representative national sample of more than 2100 adults who identified as heterosexual. Along with questions about the nature and extent of their personal relationships with lesbian and gay individuals, respondents were asked a series of questions about their general feelings toward gay men and toward lesbians, their comfort or discomfort around both and, using a standard psychological attitude scale, their general attitudes toward them.

For purposes of analysis, I divided the sample into three groups: (1) those who said they had no gay or lesbian friends, acquaintances, or relatives as far as they knew, (2) those who knew at least one gay or lesbian person but hadn’t ever talked with that individual about being gay, and (3) those who had talked with a gay or lesbian friend or relative about the latter’s experiences as a sexual minority.

Compared to Group 1, Group 2 had more positive feelings, less discomfort, and generally more favorable attitudes toward gay men and lesbians. But Group 3 had significantly more positive views of lesbians and gay men than either Group 1 (those with no personal contact) or Group 2 (those with personal contact but no open discussion).

Implications

Combined with other survey findings that I’m still analyzing, these data suggest it often isn’t enough for heterosexuals to simply know that a member of their family or immediate social circle is gay or lesbian. In order for the experience to reduce their sexual prejudice, they also must communicate directly with their friend or relative about what it’s like to be gay.

But although such discussions probably play a key role in reducing sexual prejudice and increasing support for the civil rights of sexual minorities, they can be difficult. Not surprisingly, they don’t occur often enough. In a separate study (which is not yet published), I’ve found that most gay men and lesbians say they are out to their immediate family and close heterosexual friends, but many aren’t out to their extended family, coworkers, or heterosexual acquaintances. And many of those who are out never discuss their experiences with their family or friends.

These findings highlight the importance of assisting gay, lesbian, and bisexual people in having conversations — giving them support and helping them find the best way to talk with their heterosexual friends and family members about their lives and how they’re affected by issues like marriage equality. The Tell 3 Campaign is one strategy for promoting such discussions. If the marriage equality movement is going to succeed in changing public opinion, it will have to devote more resources to Tell 3 and other programs like it.

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

More information about my 2005 survey can be found in the following chapter:

Herek, G. M. (2009). Sexual stigma and sexual prejudice in the United States: A conceptual framework. In D.A. Hope (Ed.), Contemporary perspectives on lesbian, gay and bisexual identities: The 54th Nebraska Symposium on Motivation (pp. 65-111). New York: Springer.

Copyright © 2009 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

June 12, 2009

Posted at 12:22 pm (Pacific Time)

Larry Kurdek, one of the world’s leading social science researchers on lesbian and gay committed relationships, died yesterday in Ohio.

Over the past 25 years, Larry published dozens of important empirical and theoretical articles and chapters about gay and lesbian couples. Among other findings, his research demonstrated that the factors predicting relationship satisfaction, commitment, and stability are remarkably similar for both same-sex cohabiting couples and heterosexual married couples. His work was featured prominently in amicus briefs that the American Psychological Association (APA) filed in court cases challenging marriage laws in New Jersey, Connecticut, California, Iowa, and elsewhere. He received the 2003 Award for Distinguished Scientific Contributions from the Society for the Psychological Study of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Issues (APA Division 44).

Larry helped to craft the APA’s Resolution on Sexual Orientation and Marriage, in which the Association committed itself to “take a leadership role in opposing all discrimination in legal benefits, rights, and privileges against same-sex couples.” He also helped to develop the APA’s Resolution on Sexual Orientation, Parents, and Children, in which the Association went on record opposing “any discrimination based on sexual orientation in matters of adoption, child custody and visitation, foster care, and reproductive health services.”

Larry was a great lover of dogs. After receiving his cancer diagnosis, he decided to pursue research on the emotional bonds between people and their dogs. In 2008, he published a paper titled “Pet dogs as attachment figures” in the Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. In it, he documented similarities between the attachments people form with their dogs and those they form with other humans.

According to Gene Siesky, Larry’s partner, he passed away peacefully at home with his dogs by his side, just as he had wanted.

I first met Larry back in the 1980s. I got to see him only infrequently over the years, but we had an ongoing e-mail correspondence. He gave me lots of information and guidance about my own work and writing on marriage and relationships. During the time that I chaired the Scientific Review Committee for the Wayne F. Placek Awards, he was always willing to provide thoughtful reviews of proposals. And we sent each other condolences when we lost beloved dogs.

I’ll miss Larry as both a colleague and a friend. His premature passing is a great loss to the field of psychology and to everyone who supports marriage equality.

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

John Flach, Chair of the Psychology Department at Wright State University, shared these thoughts about Larry in an e-mail:

Larry had been battling cancer for several years. Up until a few weeks ago he was still working and working out. Those of you who know Larry, know that he was very dedicated to his work and his personal fitness.

Larry will be greatly missed by his colleagues in the Psych department. In many respects, Larry was the spiritual center of our department – helping us to always focus on quality.

Larry completed the Ph.D. at University of Illinois, Chicago in 1976 and began as an assistant professor at WSU that same year. He was promoted to Professor in 1984. He was an excellent teacher – teaching courses in statistics and developmental psychology. He was a leading researcher on commitment and satisfaction in family relationships with over 145 journal publications. And he was dedicated to serving the department, college, and university. For example, he was instrumental in developing the department bylaws.

I relied heavily on Larry’s support and guidance and will personally miss him very much.

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

A viewing and memorial service will be held this weekend at Newcomer Funeral Home, Beavercreek, Ohio. In lieu of flowers, contributions can be made to the Larry Kurdek Memorial Scholarship Fund in care of the Psychology Department at Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio.

Copyright © 2009 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

May 31, 2009

Posted at 12:38 pm (Pacific Time)

Now that the California Supreme Court has upheld Proposition 8’s constitutionality, some marriage equality supporters are ready to begin collecting signatures for a new ballot measure to overturn it in next year’s election.

Instead, I hope Californians who support marriage rights for same-sex couples will take a deep collective breath and engage in level-headed strategizing about how best to achieve the long-range goal of marriage equality.

There are at least two good reasons not to put an anti-Prop. 8 measure on the 2010 ballot.

First, such an initiative stands a strong chance of losing. Highly respected statewide polls, such as those conducted by Field and the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC), indicate that support for marriage rights for California same-sex couples hasn’t increased noticeably since November. In a February Field Poll, for example, fewer than half of registered voters said they would support a new ballot measure to legalize same-sex marriage, and about the same percentage would oppose it. Only a 49% plurality said they generally support “California allowing homosexuals to marry members of their own sex and have regular marriage laws apply to them.” And a March PPIC survey found that the state’s likely voters oppose marriage equality by a 49-45% margin.

These numbers don’t bode well for a 2010 ballot campaign to overturn Prop. 8. Just over a year ago, the Field Poll found that more than half of likely voters opposed changing the state constitution to define marriage as between a man and a woman. PPIC surveys similarly revealed a widespread reluctance to enact Prop. 8. Yet that solid majority evaporated during the final months of last fall’s campaign. Launching a new initiative with support from less than half of the electorate is ill advised. And if the next campaign fails, it’s highly unlikely that the necessary resources will be available anytime soon to mount yet another ballot fight.

Second, win or lose, another initiative campaign will exact a substantial psychological toll. Research shows that marriage amendment campaigns have negative mental health effects on the people whose lives they target. A recently published nationwide study, for example, found that during the months leading up to the 2006 November election, psychological distress increased among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults living in states where an antigay marriage measure was on the ballot, but not among their counterparts living elsewhere. By Election Day, sexual minority residents of the states with antigay ballot measures had, on average, significantly higher levels of stress and more symptoms of depression than their neighbors in other states.

Comparable research on the 2008 election isn’t yet available but the limited data I’ve seen, supplemented by my own observations, lead me to believe that the Proposition 8 campaign had a similar, negative effect on many Californians. Perhaps the psychological fallout of another statewide campaign will be tolerable if Prop. 8 is repealed. But without a strong likelihood of succeeding, it is irresponsible to subject lesbian, gay, and bisexual Californians to another prolonged period of daily attacks on the legitimacy of their relationships and families.

It has become almost a cliche to assert that time is on the side of the marriage equality movement. Younger voters support marriage rights for same-sex couples more strongly than their elders (although the strength of support among young voters shouldn’t be overstated). That view will eventually achieve majority status in California, perhaps even by 2012. But almost certainly not by next year.

I’m not suggesting that marriage equality supporters should sit on their hands. There’s much work to be done to create a solid majority of California voters who feel they have a personal stake in overturning Prop. 8.

For example, heterosexuals who support marriage rights for same-sex couples can become agents of change by making their opinions known to their spouse, family, neighbors, and coworkers.

And it’s critically important for lesbian, gay, and bisexual Californians to speak directly with their straight relatives and friends about their own experiences, to explain how measures like Prop. 8 personally affect them. In the wake of the November election, the American Civil Liberties Union and other groups launched the Tell 3 Campaign to encourage and assist sexual minority adults in telling their stories to the people who love and respect them. Having such conversations is one of the most potent strategies for changing attitudes. Yet, according to my own research, they occur all too infrequently.

Last week’s Supreme Court decision has rightly evoked strong feelings among gay, lesbian, and bisexual Californians and their heterosexual supporters. That emotion can be harnessed to build a successful movement for marriage equality in California. But it shouldn’t push us prematurely into a ballot campaign that poses a significant risk not only of losing, but also of ultimately harming many lesbian, gay, and bisexual Californians.

* * * * *

A briefer version of this essay appeared in the Sacramento Bee on Sunday, May 31, 2009.

Copyright © 2009 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

November 25, 2008

Posted at 2:26 pm (Pacific Time)

Here’s how the New York Times article began:

They sat around a cafe table two days after the election, but nobody felt much like eating. It seemed like they had just been on trial. And the verdict was not pleasant.

“I feel like I’ve been kicked in the stomach,” said Lawrence Pacheco, a 23-year-old gay man. “Do they really hate us that much?”

Noting the state’s reputation for having a live-and-let-live spirit, the story reported claims by backers of the newly passed ballot measure that they didn’t intend it to discriminate against gay people. It described pre-election expectations that the amendment would fail, and discussed post-election calls for boycotts.

And the Times story noted an irony: In the same election that saw passage of the antigay measure, the state’s voters also passed a separate initiative protecting the welfare of animals.

Another story about California in the wake of Prop. 8’s passage?

No, the Times article was about Amendment 2. But not the Amendment 2 that Florida voters passed a few weeks ago, enshrining that state’s antigay relationship law into its constitution.

Rather, the Times story, which appeared in 1992, was about another Amendment 2.

Amendment 2 (version 1.0)

Sixteen years ago, by a margin of roughly 53-47%, Colorado voters passed a constitutional amendment written to overturn gay rights ordinances in Denver and other cities, and to bar the future enactment of such laws by cities or the state legislature.

Amendment 2 was ultimately struck down by the US Supreme Court in 1996. Writing for the Court majority in its historic Romer v. Evans decision, Justice Kennedy declared:

“We must conclude that Amendment 2 classifies homosexuals not to further a proper legislative end but to make them unequal to everyone else. This Colorado cannot do. A State cannot so deem a class of persons a stranger to its laws.”

Although Amendment 2 was ultimately nullified, Colorado’s gay, lesbian, and bisexual residents nevertheless had to endure the months-long antigay pre-election campaign waged by its Christian Right sponsors. And they had to deal with the knowledge that a majority of their neighbors had voted to strip them of their rights.

In the wake of the 1992 vote, a research team led by psychologist Glenda Russell conducted a statewide study to assess the psychological well-being of Colorado lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. In her 2000 book, Voted Out: The Psychological Consequences of Anti-Gay Politics, Dr. Russell reports extensive analyses of the data. In particular, she details her group’s examination of the research participants’ accounts of how they experienced the Amendment 2 campaign.

In those accounts, Dr. Russell’s group detected themes that today are all too familiar to many sexual minority residents of California, Florida, Arizona, and Arkansas. Respondents reported feeling overwhelmed or devastated by the vote. Some were shocked that the measure passed. Many experienced anger, fear, sadness, or depression. Some felt a sense of loss, saying they would never again feel the same about living in Colorado. Some expressed regret at not having done more to prevent the measure’s passage.

I can’t do justice to Dr. Russell’s book-length account here, especially her in-depth descriptions of the stories related by research participants. But one of her important findings was that a substantial segment of the sample reported many symptoms that are commonly associated with depression, anxiety disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and they perceived that these symptoms were a direct result of having lived through the months of antigay campaigning.

Thus, the data are consistent with the conclusion that antigay campaigns not only take away individuals’ rights, but are also harmful to the mental health of the gay, lesbian, and bisexual people who live through them.

The 2006 Anti-Marriage Campaigns

After the Supreme Court’s Romer decision, antigay activists soon found another focus for their efforts.

Following a Hawaii court ruling that seemed to portend the extension of marriage rights to same-sex couples in the Aloha State, religious and political conservatives shifted their focus to the goal of preventing marriage equality from becoming a reality. In 1996, Congress passed and then-President Bill Clinton signed the so-called Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), and antigay organizations directed their energies to passing state-level DOMAs across the country.

The DOMA campaign proved to be a powerful strategy. Not only did the statewide measures consistently win by large majorities, they also brought out voters who helped to elect Republicans to office. The Christian Right was able to use the campaigns to increase its strength within the Republican party — and in many Republican-controlled quarters of government — while promoting its antigay agenda.

Meanwhile, gay and lesbian and bisexual people living in the targeted states endured rhetorical — and sometimes physical — attacks against themselves and their families.

In 2006, marriage amendments appeared on the November ballot in 8 states. All of them passed except in Arizona. (The Arizona measure’s defeat was widely attributed to ambiguities concerning whether it would adversely affect heterosexual couples; a rewritten version that focused exclusively on banning recognition of same-sex relationships passed on November 4.)

Given the earlier findings of Dr. Russell’s research team in Colorado, it was reasonable to assume that those campaigns in other states would also exact a psychological toll. That hypothesis is supported by data from a new study to be published early in 2009 in the prestigious Journal of Counseling Psychology.

The study, titled Marriage Amendments and Psychological Distress in Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual (LGB) Adults, was conducted by Drs. Sharon Rostosky, Ellen Riggle, Sharon Horne, and Angela Miller.

Through Internet surveys, the researchers used standard mental health measures to assess the current well-being of more than 1500 lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. For example, respondents were asked whether they had recently experienced various symptoms of depression, such as having difficulty sleeping or concentrating, feeling fearful or hopeless, and not being able to “get going.” They were also asked about the extent to which they were experiencing negative emotions, such as fear, irritability, hostility, and nervousness.

587 participants completed two versions of the questionnaires — one in the spring of 2006 and a second one about 6 months later, shortly after the November elections. Nearly one thousand others completed the post-election questionnaire, but not the pre-election survey.

The researchers sorted participants into two groups — those living in a state with an anti-marriage amendment on the 2006 November ballot and those in other states. Not surprisingly, compared to residents of other states, residents of the amendment-campaign states reported encountering a larger number of antigay messages in the mass media and in day-to-day conversations. Moreover, comparison of the November questionnaires with those administered six months earlier revealed that the number of encounters with negative messages had increased significantly in the amendment states but not in the other states.

When the researchers examined the mental health data, they found that residents of the states where an antigay campaign had just been waged reported higher levels of stress, more negative emotions, and more symptoms of depression than did respondents who lived elsewhere. Comparison of the pre-election and post-election questionnaires revealed that levels of psychological distress had increased significantly among residents of states with a marriage amendment on the ballot, but not among residents of other states.

In sum, the findings of Dr. Rostosky’s group support and extend those of Dr. Russell’s research team. By examining the experiences of sexual minority adults residing in different states, and by comparing scores on mental health measures before and after the statewide antigay campaigns, they provide good evidence that marriage amendment campaigns are harmful to the mental health of lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals.

Strategies for Coping and Healing

As with my summary of Dr. Russell’s research, a brief blog entry can’t do justice to the findings of Dr. Rostosky and her colleagues. But in the wake of the recent antigay votes, even this short synopsis of their work may be helpful to many lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals.

If you were touched by the campaigns in California, Arizona, Florida, or Arkansas, and if you’ve been experiencing post-election psychological distress — whether it takes the form of anger, sadness, irritability, feelings of betrayal, revenge fantasies, sleep difficulties, or something else — the research suggests you’re not alone. What you’re feeling these days is a natural and normal response to the attacks you endured during the months leading up to November 4, and to the trauma of election night.

What can you do about it? Different people have different coping styles so there isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution. Moreover, as a nonclinician, I don’t have the expertise to offer mental health advice. But I believe it’s important to understand that the research described above not only documents the damage inflicted by antigay ballot campaigns — it also shows that lesbian, gay, and bisexual people are remarkably resilient in dealing with those assaults.

Antigay attacks have a long history, and many participants in the Rostosky team’s study who didn’t reside in a state with a 2006 marriage amendment nevertheless had endured earlier marriage amendment battles. Their relatively low levels of psychological distress indicate they had recovered over the years from those negative campaigns.

In terms of facilitating such recovery, Dr. Rostosky and her coauthors suggest that sexual minority individuals should avoid blaming themselves or accepting antigay stigma and prejudice as valid. Instead, it’s important to remind oneself that the people who foment antigay hostility are the ones who deserve blame.

They also point to the importance of actively focusing on positive events and messages in one’s environment, and increasing one’s exposure to these messages by building stronger relationships and social support networks. This doesn’t mean engaging in self-deception or denying reality. But it’s important to find areas in your life that are positive and affirming, and to give yourself permission to take a break from dealing directly with prejudice and stigma to the extent that you can.

If you’ve been religiously reading every on-line posting about Proposition 8 and the other ballot measures, for example, maybe you should stop for awhile. Or perhaps you should at least consider restricting your reading to news stories while bypassing the blogs and comments that attack same-sex couples and marriage equality.

A strategy that many people use is to actively take control of how they think about their experiences with the ballot measures, and to put those experiences in a broader context. Related to this approach, in a 2003 article coauthored with Jeffrey Richards, Dr. Russell argued for the importance of adopting a “movement perspective — a view that sees LGB experiences as part of a larger social and political movement.”

“In the first place, adopting a movement perspective is helpful to LGB people in the political realm. For example, it supports the creation of coalitions with other oppressed groups and provides a historical framework within which to understand a particular event as but one element of an enduring movement for social change…. Adopting such a perspective allows LGB people to understand the relevance of homonegativity to their own lives, thereby decreasing the likelihood that they will be shocked by the overt presence of antigay political rhetoric and actions. Having a movement perspective also allows LGB people to place some undeniably painful experiences — rejection by family members, for example — into a broader and perhaps less personalized context” (p. 326).

Adopting such a perspective might lead you to engage in more activism — for example, by organizing and participating in rallies and protests, or getting involved with local and statewide political groups that are working for sexual minority rights. Many people who have attended post-election No On Prop. 8 rallies report they’ve felt better as a consequence.

At the same time, activism can lead to more encounters with antigay messages and, consequently, more stress. Indeed, Dr. Rostosky and her colleagues found that survey respondents who reported high levels of political activism during the anti-amendment campaigns were at greater risk than others for psychological distress. So here, too, it’s important to take control over your experiences as much as you can, and to develop a strategy for activism that can sustain you for the long term.

Colorado’s Amendment 2 was eventually overturned by the US Supreme Court. And although the losses on November 4 were devastating, it’s important to recall that the election also brought many positive changes. In 2009, a new Congress and a new Administration will assume leadership in Washington, and they have already indicated their willingness to end many forms of discrimination against sexual minorities at the federal level.

And that is cause for hope.

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

You can read more about Dr. Glenda Russell’s research in these sources:

- Russell, G. M., & Richards, J. A. (2003). Stressor and resilience factors for lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals confronting antigay politics. American Journal of Community Psychology, vol. 31, pp. 313-328.

The article by Dr. Sharon Rostosky and her colleagues will be published early in 2009. Here is the reference, with a link to the pre-publication page proofs:

- Rostosky, S. S., Riggle, E. D. B., Horne, S. G., & Miller, A. D. (2009). Marriage amendments and psychological distress in lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) adults. Journal of Counseling Psychology, vol. 56, #1.

For more information about Colorado’s Amendment 2, and the Christian Right’s campaigns against the sexual minority community, see:

Copyright © 2008 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

November 8, 2008

Posted at 1:37 pm (Pacific Time)

Was the passage of Prop. 8 always a foregone conclusion, despite poll results throughout the summer and early fall showing most likely voters opposed it?

Or were the major polls correct, and the sentiment of California voters actually shifted in the weeks leading up to Election Day, from opposition to support?

Some Prop. 8 supporters maintained throughout the campaign that survey results consistently understated support for their side because many respondents wished not to appear bigoted to a pollster. They cited a “study” they had conducted with polling data from previous state anti-equality campaigns to support their argument.

And Lorri L. Jean, executive director of the Los Angeles Gay & Lesbian Center, asserted in a September letter to marriage equality supporters that:

There is typically a 7-10 point difference between what people tell the pollster about their views on LGBT rights and how they really vote. In other words 7-10% say they believe in equality but actually vote against us.

The existence of a racial Bradley effect — i.e., a pattern in which the polls’ accuracy is affected by significant numbers of racist Whites lying to pollsters and saying they would vote for a Black candidate — has been widely disputed, and wasn’t evident in polling this year.

But was there a gay Bradley effect in California?

In a September article in The Advocate, political scientist Patrick Egan answered this question in the negative, concluding that voters were largely telling pollsters the truth. “If any such reluctance [to tell the truth] exists with regard to same-sex marriage initiatives,” Egan said, based on his examination of polling data from previous campaigns, “it is small — about two points on average since 1998. In 2006 it was effectively zero.”

Now that the election results are in, we can compare the actual vote tallies to the last Field poll before Election Day. My own reading of the data is that they reveal no evidence that survey respondents said they would vote No when they actually supported the measure.

The final Field Poll, conducted about one week before the election and released on October 31, indicated that 49% of likely voters opposed the measure. The margin of error was +/- 3.3 points, so the poll’s estimate was that opposition in the population of California voters ranged between 46% and 52% at that time.

The official tally so far (which still excludes some absentee and provisional ballots) puts the actual No vote at 48%, well within the range of the Field Poll’s estimate.

The same Field Poll found that 44% of likely voters supported Prop. 8 a week before the election, and another 7% were undecided. Factoring in the margin of error, the poll’s estimate of the actual population proportions ranged as high as 47% for the Yes side, with anywhere from 4-10% undecided.

These numbers fall short of the final Yes tally, but it’s not difficult to construct a scenario whereby they are consistent with the Prop. 8 win on Election Day.

First, if most of the undecideds ultimately voted Yes (the pattern that apparently occurred with antigay Prop. 22 in 2000), the result would have been close to what happened on Tuesday.

Add to this the fact that the No vote was trending downward in the weeks leading up to the election. Polls by Field and the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) estimated that opposition was around 55% in September. But it declined to 52% in an October PPIC poll and 49% in the final Field Poll a week later. To the extent that those declining numbers indicated that “soft” No voters were in the process of switching to the Yes side, it would help to account for the election day outcome.

Finally, turnout in this election was unusually high, especially among groups that historically haven’t voted in large numbers. This created unique challenges for pollsters in identifying likely voters. To the extent that the criteria used by the various survey organizations to estimate turnout in advance of Election Day were inaccurate — especially among key voter groups — their figures would have missed the mark.

In the final Field Poll, for example, African Americans were projected to constitute about 6% of likely voters, and a plurality of about 49% said they supported Prop. 8; another 9% (roughly) were undecided. These figures were derived from interviews with a fairly small number of Black respondents, so the margin of error was substantial (perhaps as much as +/- 12 points) and generalizing from them is risky. If we simply take them at face value, they suggest that Blacks’ contributions to the total vote a week before the election was about 3 points on the Yes side, and slightly less on the No side. Taking the margin of error into account, however, Blacks’ support for Prop. 8 could have ranged as high as 60%. And the undecideds could have subsequently added even more to that total — especially if they were persuaded to vote Yes by appeals from the pulpit on the Sunday before Election Day.

Exit polls were consistent with the latter scenario, finding that about 70% of Blacks ultimately voted Yes. Moreover, they constituted 10% of voters — not 6% — making the impact of their opposition considerably stronger.

It’s important to remember that exit polls — like any survey based on a sampling of the population — have a margin of error associated with their estimates. And the margin can be large for relatively small groups. In the case of Blacks’ votes, the exit poll’s error is probably +/- 5 to 6 points, and there remains the bigger question of whether the specific precincts that were sampled yielded an accurate reflection of African Americans statewide.

Nevertheless, it seems safe to assume that Blacks ultimately provided substantial support for the Yes side — perhaps enough to account for the election outcome. Most likely, there are other groups for whom turnout projections were also incorrect and, in combination with the downward trend in No voters and last-minute decisions by undecideds, these factors can probably account for the disparities between pre-election polling and the actual outcome.

Thus, it’s difficult to conclude that significant numbers of Prop. 8 supporters lied to pollsters and said they were planning to vote No. Perhaps some Yes voters disingenuously told researchers they were undecided, but it’s equally plausible that most undecideds truly didn’t make up their minds until late in the campaign, perhaps not until Election Day.

At any rate, the so-called “study” that Prop. 8 supporters posted on their web site in mid-September and promoted to the media as evidence of the “gay Bradley effect” can’t really be taken seriously. Even a cursory examination of the polling data they used reveals several glaring problems:

- They ignored the polls’ margin of error. In more than 40% of the polls cited in the “study,” the discrepancy between the poll estimate and the actual vote was 5% or less. For many statewide polls, this is within the margin of error.

- They only noted undercounts in the anti–equality vote, suggesting that all discrepancies resulted from voters telling pollsters they supported the right of same-sex couples to marry but then voting against marriage equality. But in many of the polls listed in their spreadsheet, the actual vote counts against the anti-gay measures also were higher than the polls’ estimates. How can this be? The answer lies with the undecided poll respondents. They had to make a decision in the voting booth and they tended to favor the winning side — which was anti-equality in all cases except the 2006 Arizona campaign.

- They included polls that were conducted weeks (in some cases, months) before the election. As all pollsters know, surveys are usually more accurate to the extent that they’re completed close to voting time. But the “study” included polls that were published more than a month before election day.

- They were selective in which polls they picked. For example, in the 2004 Arkansas election for Amendment 3, the “study” used an October Zogby poll, which indicated that 65% of respondents supported the amendment. But an Opinion Research Poll released in late October found that 77% of Arkansas voters supported Amendment 3, slightly more than actually voted for it.

In summary, I don’t believe that the findings of the PPIC and Field Polls leading up to the election were wrong. Rather, I suggest we assume that a majority of typical California voters truly were opposed to eliminating the right of same-sex couples to marry throughout the summer, but their numbers began eroding by October. Among actual voters, supporters of Prop. 8 came to outnumber opponents by Election Day, albeit by a surprisingly small margin. (Recall that just 8 years ago Prop. 22 won by more than 20 points.)

Thus, we can use the PPIC and Field Poll data as a tool for better understanding how the various strategies pursued by each side between May and November ultimately affected the outcome of the election.

Copyright © 2008 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

October 31, 2008

Posted at 2:51 pm (Pacific Time)

Just in time for Halloween, the latest Field Poll brings some scary news for marriage equality supporters. But the results might also create a well-founded sense of foreboding among those who oppose marriage equality and want to write their views into the California constitution.

The poll indicates the Proposition 8 race has tightened considerably. Support for the constitutional amendment still hasn’t reached the 50% mark, but opposition has dropped to 49%.

Moreover, the 5-point gap between the 44% of likely voters who support Prop. 8 and the 49% who oppose it is now within the poll’s margin of error of +/- 3.3 points. In other words, the true proportion of YES voters in the population could range as high as 47.3% and the true number of NO voters could be as low as 45.7%.

About 7% of likely voters are still undecided.

Examining Trends

Ten days ago, I posted an analysis of the Proposition 8 polls conducted by Survey USA, and concluded that they probably undercounted Prop. 8 opponents but gave a more or less accurate reading of the number of the measure’s supporters. A few days later, data from a new Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) poll supported that hypothesis. It showed that the race had tightened, but opponents still led supporters, 52% to 44%.

In statistical terms, the newest numbers from the Field Poll aren’t significantly different from the October PPIC findings — that is, when the respective polls’ margins of error are considered, their estimates of the proportion of YES voters in the California population overlap, and their estimates of the NO voters match.

When we look at the two polls in tandem, however, it appears that the NO position has eroded somewhat and now hovers around 50%. And the YES side appears to have increased its numbers substantially during the past month.

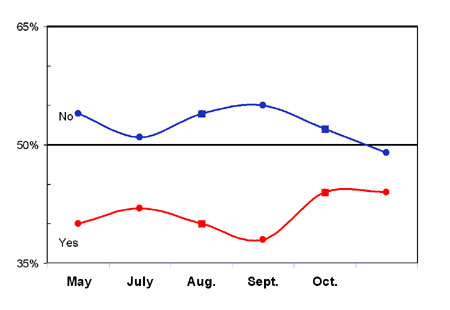

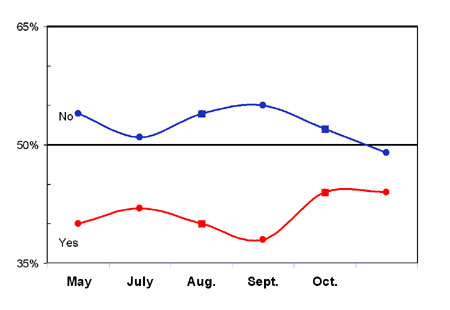

The graph below shows the trends in voters’ attitudes toward Prop. 8 since last May, using data from four statewide Field Polls (filled circles) and two PPIC polls (filled squares). In combination, the polls indicate the race was fairly stable until September, when both sides inaugurated their media campaigns (and when voter interest in the election traditionally begins to rise). At that point, support for Prop. 8 began to increase steadily (from 38% in September to 44% in October), while opposition declined (from a high of 55% to the latest figure of 49%).

Keep in mind that the data in the graph come from two different survey organizations, that somewhat different question wordings were used in different polls, and that all of these figures have a margin of error (ranging from about 2-4 points) associated with them.

Nevertheless, the new Field Poll data indicate that the race is much closer now than at any time since the California Supreme Court issued its historic ruling last May. Prop. 8 opponents have lost the comfortable lead they held throughout the summer.

On the other hand, Prop. 8 proponents have yet to register support from a majority of the public, which the amendment needs in order to pass.

Who’s Voting For and Against Prop. 8?

Compared to the September Field Poll, support for Prop. 8 appears to have increased in the Central Valley (where it’s now leading by a margin of 53-42%) , but also in Los Angeles, where it’s now losing by a plurality of only 48.5% to 43% — within the poll’s margin of error. By contrast, the September Field Poll found it to be losing in Los Angeles by nearly 25 points.

Support for Prop. 8 has increased to 75% among Republicans, but opposition among Democrats has dropped to 65%. Democrats outnumber Republicans by a margin of 44% to 34%, so this split still favors the NO side in terms of the raw vote count. But the fact that Democrats comprise about one fourth of the YES voters is a cause for concern among Prop. 8 opponents.

On the bright side for opponents, Independents and members of other parties still oppose Prop. 8 by a 2-to-1 margin, and political moderates oppose it 50.5% to 40%.

Consistent with previous surveys, women oppose Prop. 8 by a margin of 50.5% to 42%. However, men are now evenly split, 47% NO to 46% YES. The Proposition trails by margins of about 10 points among all age groups except voters who are 65 and older, among whom it is winning, 62% to 32%.

Given recent speculation about racial and ethnic differences in voting patterns, it is somewhat surprising that Latinos don’t differ substantially from non-Hispanic Whites — pluralities of both groups oppose Prop. 8. African Americans support the amendment by a plurality, while Asian Americans oppose it by a slight majority. However, corresponding to their representation among registered voters, the absolute numbers of African Americans and Asian Americans in the sample are fairly small and, in combination, they appear to cancel each other out.

A plurality of Catholics opposes Prop. 8, while Protestants support it by a margin of 60% to 33%. Within the latter group, three-fourths of self-described born-again Christians support it (59% of non-born-agains oppose it). The proposition is opposed by strong majorities of the non-religious (77%) and those affiliated with “other” religions (64%).

Most poll respondents (78%) said they personally know or work with someone who is gay or lesbian, and 51% of those respondents say they will vote NO. By contrast, 50% of respondents who say they don’t know gay people personally are planning to vote YES. Based on my own research, I speculate that opposition to the amendment is strongest among respondents who have actually discussed Prop. 8 (or other issues related to sexual orientation) with a gay or lesbian friend or family member. However, the Field Poll didn’t include a question about such conversations.

The survey also indicates that opponents of Prop. 8 are more likely than supporters to be planning to vote at their local precinct on Tuesday. Both sides are about equally represented among absentee voters, but more supporters than opponents say they’ve already mailed in their ballot. If that pattern persists, Prop. 8 opponents will begin Election Day with a deficit in absentee ballots that will have to be balanced by votes cast in the precinct polling places.

Related to this point, Obama supporters — who constitute 55% of California voters, according to the Field Poll — are disproportionately likely to vote NO on Prop. 8 (73% versus 21% who will vote YES). McCain voters are less numerous (33% of California voters) and they support Prop. 8 by an 84% to 13% margin. Thus, the Obama campaign’s get-out-the-vote effort may help to defeat Prop. 8. But Obama supporters who oppose Prop. 8 account for only about 40% of likely voters (73% of 55% = 40%).

Which Arguments Are Persuasive?

In addition to estimating the proportions of YES and NO voters, the latest Field Poll asked respondents whether they agreed or disagreed with various arguments for and against Prop. 8. Roughly half of the respondents were asked about each statement.

When interpreting these data, it’s useful to keep in mind that survey researchers often observe an “acquiescence bias.” When presented with assertions about an issue, poll respondents — especially those who don’t have strong opinions or are undecided — are more likely to agree than to disagree. There are many explanations for this pattern, including the generally plausible nature of most agree-disagree statements presented in surveys, the amount of mental effort it takes to marshal counter-arguments to them, and most respondents’ desire to be polite and agreeable.

Thus, it’s not unusual to find some respondents who agree with seemingly contradictory statements in the same survey.

Illustrating this pattern, 65% of the sample agreed that “The institution of traditional marriage between a man and a woman is one of the cornerstones of our country’s Judeo-Christian heritage,” which would appear to indicate strong support for the YES side. More than two thirds of undecided respondents agreed with this statement, as did 90% of YES voters and 39% of NO voters. (Recall that undecided voters constitute only 7% of the sample, so percentages from this group aren’t very reliable.)

But majorities also agreed with the following statements that appear to support the NO side:

- 58% agreed that “Matters relating to the definition of marriage should not be written into the constitution.” (Most undecided voters agreed, as did 74% of NO voters and 41% of YES voters.)

- 57.5% agreed that “Domestic partnership laws by themselves do not give gay and lesbian couples the same certainty and security that marriage laws provide.” (Half of undecided voters agreed, as did 72% of NO voters and a 45% plurality of YES voters.)

- 57% agreed that “Extending new rights and legal protections to different peoples and lifestyles, such as gays and lesbians, benefits California and the nation in the long run.” (A plurality of undecided voters agreed, but almost as many were unsure about this statement.)

- 61% agreed that “By eliminating the right of gay and lesbian couples to marry, Prop. 8 denies one class of citizens the right to enjoy the dignity and responsibility of marriage.” (Undecided voters were closely divided on this statement.)

In light of the acquiescence bias, the statements with which most respondents disagreed are especially noteworthy:

- 60% of the sample disagreed that “If Prop. 8 is not approved, the public schools could be required to teach kids that same sex marriage is as acceptable as traditional marriage in California.” (More than two thirds of undecided and NO voters disagreed, as did a 48% plurality of YES voters.)

- 59% of the sample disagreed that “Gay rights leaders in California are moving too fast in their efforts to win new rights and legal protections for gays and lesbians.” (Most undecided voters disagreed, as did 87% of NO voters.)

And some other arguments favoring the YES side were endorsed by only a plurality or a bare majority, with a fair proportion of undecideds:

- 50% agreed that “Prop. 8 restores the institution of traditional marriage between a man and a woman, while not removing any domestic partnership rights that had previously been granted to gay or lesbian couples” (Majorities of undecided and YES voters agreed, as did 23% of NO voters; but many undecideds were unsure about this statement.)

- A 47% plurality of the sample agreed that “Prop. 8 reverses the flawed legal reasoning of activist judges who overturned the state’s previous voter-approved law defining marriage as between a man and a woman.” (While 73% of YES voters agreed, along with 26% of NO voters, most undecideds either disagreed or were unsure.)

But one argument from the NO side also evoked considerable uncertainty:

-

A 40% plurality agreed that “Followers of the Mormon Church are exerting too much influence on the state’s political process by underwriting an estimated 40 percent of the Yes on Proposition 8’s campaign contributions.” (While 55% of NO voters agreed, about half of undecideds and 29% of YES voters were unsure.)

Overall, these response patterns suggest that likely voters tend to endorse arguments that support their position, but many also accept arguments that appear to contradict their own stance. The NO side apparently has been effective at persuading most California voters that the YES side’s claims about schools and schoolchildren are incorrect. And more arguments in support of a NO vote receive majority support than do the arguments supporting a YES vote.

So why is the race so close?

Old Prejudices Die Hard

It’s noteworthy that this question is even being posed. Back in May, I would have been very surprised to know that Prop. 8 would be trailing in the polls just a few days before the election.

Perhaps instead we should be remarking on the fact that so many voters have proved reluctant to write antigay discrimination into the California constitution. The widespread opposition to Prop. 8, and the fact that proponents of the measure have been so careful not to publicly bash sexual minorities, are signs of a sea change in public attitudes.

Nevertheless, old prejudices die hard. Gay, lesbian, and bisexual people are still stigmatized throughout the United States and in much of California. Powerful groups — including the Mormon Church and Focus on the Family — have dedicated their vast resources to perpetuating sexual stigma. And many heterosexuals with generally enlightened attitudes are still uncomfortable thinking about same-sex relationships.

In my own research, I’ve found that heterosexuals’ opinions about marriage equality are very closely linked to their general attitudes toward gay men and lesbians. Other factors are also important — including religious beliefs and political values — but antigay attitudes are usually the strongest predictor of marriage attitudes.

It would be surprising if antigay prejudice weren’t playing an important role in the California election. Such prejudice — coupled with the barrage of pro-Prop. 8 messages that many Californians have been getting from their religious leaders — may well account for the closeness of the contest, even though so many voters say they agree with key arguments against Prop. 8.

Nevertheless, Prop. 8 still has a good chance of being defeated. But the Field Poll results highlight the importance of swaying voters who are still undecided, and turning out the vote among Prop. 8 opponents.

If you oppose Prop. 8, no matter where you live, my advice is to talk (in person, on the phone, via e-mail) with your California friends, family, roommates, classmates, coworkers, and neighbors this weekend. Urge them to vote NO and, if you’re a California voter, tell them why you’re casting your vote against Prop. 8. The No On 8 website has some tools to assist with e-mail outreach.

And then do everything you can to ensure that they vote by Tuesday evening at 8 pm.

* * * * *

The most recent survey report can be downloaded from the Field Poll website.

Copyright © 2008 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

October 21, 2008

Posted at 6:02 pm (Pacific Time)

Ever since California county clerks began issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples last June, Proposition 8 — the proposed constitutional amendment to eliminate marriage equality — has appeared likely to lose at the ballot box. Throughout the summer, statewide surveys from the Field Poll and the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) consistently found that the measure lacked majority support. In fact, it was opposed by more than 50% of likely voters.

But earlier this month, a new poll of Californians’ voting intentions on Proposition 8 was released, sponsored by several CBS local affiliates and conducted by SurveyUSA. Here’s a section of the news report on the poll findings:

According to the poll, likely California voters overall now favor passage of Proposition 8 by a five-point margin, 47 percent to 42 percent. Ironically, a CBS 5 poll eleven days prior found a five-point margin in favor of the measure’s opponents.

The only demographic group to significantly change their views during this period were younger voters — considered the hardest to poll and the most unpredictable voters — who now support the measure after previously opposing it.

Last week, the same survey organization released new data showing that the ballot race is a statistical dead heat, with 48% supporting Prop. 8 and 45% opposing it (the margin of error is +/- 4 points).

In combination, these polls indicated a surprising shift in California opinion, and they received a lot of media attention. The No On 8 campaign publicized them to warn Californians that Proposition 8 has a serious chance of passage and to galvanize marriage equality supporters to donate to the campaign. Many couples moved up their wedding date in order to have their marriage officially recorded before the election, banking on Attorney General Brown’s opinion that Proposition 8, if passed, won’t apply retroactively.

A Closer Look At Those Data

I certainly agree that the race will probably tighten as November 4 approaches. A September Field poll revealed that voters who haven’t previously thought much about Proposition 8 can be swayed by the measure’s wording on the ballot. And the multi-million dollar media campaign that is now being waged is likely to have already influenced some voters. Thus, in the next two weeks, undecided voters will make their choice, and some “soft” supporters and opponents of the measure will change their minds.

So marriage equality supporters can’t afford to be complacent. Nevertheless, I’d like to register my skepticism about the recent polling data.

The polls showing Prop. 8 winning or tied were conducted by SurveyUSA, a New York firm that specializes in automated surveys. These are surveys that don’t use a human interviewer. Instead, when someone answers the phone, they hear a prerecorded voice (perhaps a local newscaster) asking them to use the telephone keypad to register their answers to a few questions.

According to its website, SurveyUSA:

is the first research company to appreciate that opinion research can be made more affordable, more consistent and in some ways more accurate by eliminating the single largest cost of conducting research, and a possible source of bias: the human interviewer.

The company claims that its polls are superior to others because they eliminate the variability in quality that results from having human interviewers.

A point not mentioned on their website is that many people have a tendency to hang up when they answer the phone and hear a recorded voice. Another problem is that, because no human interviewers confirm a respondent’s eligibility, anyone who answers the telephone — a child or teenager, a babysitter, an out of town guest — can complete the survey. These factors might affect the accuracy of SurveyUSA data.

On the other hand, survey participants are sometimes more willing to reveal potentially sensitive or embarrassing information about themselves to a computer than to a human interviewer. A 2006 study, for example, found that adults were more likely to acknowledge having had sex with a person of their same sex when the interview was conducted via computer rather than with a live interviewer. But it’s not clear that a significant number of Californians are reluctant to say whether they support or oppose Prop. 8. And, unlike SurveyUSA polls, the 2006 survey was first introduced and explained to respondents by a live interviewer.

Comparing Polls

To repeat a recurring theme of this blog, any poll is merely a snapshot of public opinion at one moment in time. Because opinion can shift and polls vary in their accuracy, it’s important to evaluate a survey’s findings in comparison to other polls that addressed the same topic.

So here are the SurveyUSA findings:

June 9: 44% support, 38% oppose (18% undecided)

September 25: 44% support, 49% oppose (7% undecided)

October 6: 47% support, 42% oppose (10% undecided)

October 17: 48% support, 45% oppose (7% undecided)

For comparison purposes, here are the results from the Field and PPIC polls:

May 28 (Field): 42% support, 51% oppose (6% undecided)

July 18 (Field): 42% support, 51% oppose (7% undecided)

August 27 (PPIC): 40% support, 54% oppose (6% undecided)

September 18 (Field): 38% support, 55% oppose (7% undecided)

September 24 (PPIC): 41% support, 55% oppose (6% undecided)

All of the polls show support for Proposition 8 hovering in the low-to-mid 40s, except the most recent SurveyUSA data, which have it gaining – but still not at 50%.

Where they disagree the most is in their estimates of the proportion of Californians who oppose Prop. 8. The Field and PPIC polls put opponents in the majority. Survey USA has them ranging between 38% and 49%.

Election polls can differ for many reasons, including how questions were worded, when the poll was fielded, and how the survey organization defined what constitutes a “likely voter.” Activists and pundits have assumed that the dramatic differences between the SurveyUSA polls and the PPIC and Field polls reflect a real shift in public opinion. They attribute that shift to the Yes On 8 media campaign — which has included images of San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom gleefully proclaiming that marriage equality is here “whether you like it or not,” as well as inaccurate claims that failing to pass Proposition 8 will lead to the harassment of churches and pro-gay indoctrination of children.

Those ads may indeed have affected undecided voters and Californians whose opposition to Prop. 8 wasn’t strong. But my guess is that the big difference between SurveyUSA and the Field and PPIC polls lies in the quality of their samples.

The Field and PPIC polls are conducted over a longer time period. This usually results in better data because more people in the original sample are reached than is possible when a poll is in the field for only one or two days. When Field and PPIC researchers don’t reach a respondent on their first attempt, they phone back at least five times.

With overnight and 2-day polls, by contrast, anyone who isn’t home on the first or second try is simply dropped from the sample. This creates an accuracy problem if those people differ from the poll respondents in a way that is relevant to the survey question — in the case of Prop. 8, for example, if they are younger or more liberal than the people who happened to be home when the phone rang. Pollsters try to account for the missing respondents by mathematically weighting the data, but this always involves guesswork.

A second strength of the Field Poll sample is that it’s drawn from official voter registration lists, and respondents are contacted through the address and phone number they provided when they registered. So the Field Poll sample includes registered voters who rely mainly or exclusively on a cell phone. By contrast, the SurveyUSA and PPIC samples were selected through random-digit dialing (RDD), a method widely used in telephone surveys. Individuals without a land line are almost always excluded from RDD samples.

Are cell phone users different from other voters in a way that is relevant to Prop. 8? Maybe. Data from the Pew Research Center suggest that samples based exclusively on land-line calling probably underestimate support for Barack Obama by about 2 percentage points because Obama has a disproportionate amount of youth support, and many young voters rely exclusively on cell phones.

More to the point, Pew researcher Scott Keeter and his colleagues used data from a national survey that included cell-phone users to compare the opinions of adults under 30 on a range of topics. They found that only 37% of young adults in land-line households supported marriage equality, compared to 51% of those who relied on cell phones.

Keeter also found that Pew statisticians were able to effectively compensate for this discrepancy by applying statistical weights to the data from land-line surveys.

We don’t know if SurveyUSA weighting procedures are comparable.

Relevant to this point, the recent SurveyUSA polls have found that voters under 35 either strongly support Proposition 8 (by a margin of 53% to 39% in the October 6 poll) or are closely divided (44% Yes to 46% No in the October 17 poll). By contrast, most polls in California and elsewhere have found that young adults generally favor marriage equality. In my mind, this raises some doubts about the accuracy of the SurveyUSA data.

On Balance…

My own guess is that the Field Poll, by virtue of its sample drawn from the voter registration rolls, probably describes current opinion among California voters more accurately than the SurveyUSA data. The fact that the PPIC poll data have closely tracked the Field Poll results over the summer further boosts my confidence in both surveys. I suspect that the SurveyUSA data are more or less accurately stating the number of likely voters who support Prop. 8, but are undercounting the number who oppose it.

But this is only an educated guess. We’ll have a better sense of current California opinion on the ballot measure when the next round of PPIC and Field Poll results are released, which is likely to be soon.

Meanwhile, even if the SurveyUSA results have important limitations, they highlight two key facts.

First, many Californians are still making up their minds about Prop. 8 and can be swayed during the next two weeks by conversations with their friends and family, endorsements by public figures whom they respect, and media campaigns. This means it’s important for marriage equality supporters to continue to donate to the No On 8 campaign, to declare their opposition to Prop. 8 in public forums, and to personally explain their views about the measure to their friends and family.

Second, voter turnout will be critical. Regardless of whether most Californians support or oppose Proposition 8 today, what truly matters is who votes — whether by absentee ballot, in early voting, or at their polling place on November 4th.

Thus, equality supporters should make sure that their friends, family, roommates, classmates, coworkers, and neighbors vote.

* * * * *

For more information about surveys and cell phones, see the article by Scott Keeter et al., “What’s Missing from National Landline RDD Surveys?: The Impact of the Growing Cell-Only Population,” in Public Opinion Quarterly, 2007, vol. 71(#5), pp. 772-792.

Copyright © 2008 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

« Previous Page — « Previous entries « Previous Page · Next Page » Next entries » — Next Page »